26 July 2025, Nick Saperov

Introduction: Why The Open-Source Matters and Soviet Union Failed

The renowned economist John Maynard Keynes famously said, “Money matters”. In the world of software development, I have my own version: “Open-source matters”. The principle is the same. Open-source is to the health of a software ecosystem what the circulation of money is to an economy – it enables growth, innovation, and freedom.

But what exactly is ‘open-source’? Simply put, all software is built from code—a set of human-written instructions that a computer reads to perform a task. This code can be proprietary, or ‘closed.’ Think of Instagram; its code is the exclusive property of Meta. If you, an ambitious developer, had a brilliant idea for Instagram 2.0, you couldn’t access the original code. You would have to rebuild it from scratch, an impossibly impractical task. The digital doors are locked.

Open-source software is the opposite. The core code is publicly accessible. You can freely take it, study it, modify it, and build upon it. At first, this seems counter-intuitive. Why would a developer who spent countless hours and their last dollar on a project simply give the code away?

The answer lies in the long-term vision, and it’s best explained by an analogy I know from personal experience. My childhood coincided with the final years of the Soviet Union, and I vividly remember what a command economy feels like. A central authority, the Politburo, made every economic decision: what to produce, in what quantity, and at what price. The result was a constant ‘deficit’—not just of toys and clothes, but of basic foods. Over time, the central planning apparatus grew ever more disconnected from the real needs of the people.

A closed-source software project risks the same fate. The controlling company, like a Politburo, dictates the product’s entire future. It can become slow, unresponsive to user needs, or be abandoned altogether.

Open-source, however, operates like a market economy. Anyone, from a seasoned professional to a curious student, can identify a potential improvement, take the existing code, and build something better. It is a system built on freedom, collaboration, and merit. This philosophical alignment is the single biggest reason I chose the open-source WordPress framework for my portfolio.

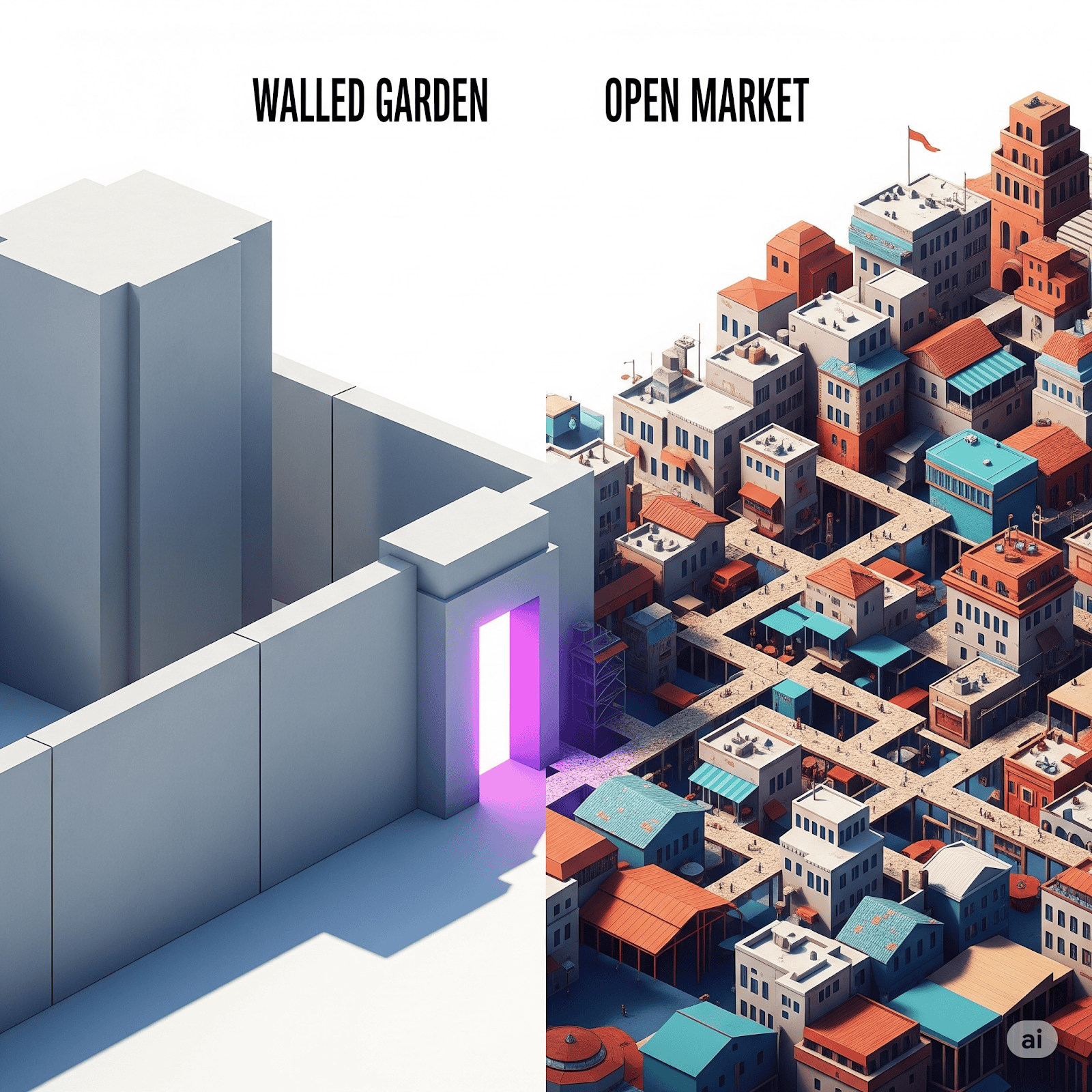

WordPress vs. The Walled Gardens (Wix, Tilda)

After launching my portfolio website, I shared it with friends for feedback. The most important question came from my friend, Serhii. “Why WordPress,” he asked, “and not Tilda?”. My immediate answer was brief: “Because it’s open-source”. This article is the detailed explanation I promised him.

It’s a fair question. Website builders like Tilda, Wix, and Squarespace are incredibly popular, and their main advantage is convenience. They allow you to construct an entire website by simply dragging and dropping blocks, much like playing with LEGOs. Almost anyone can build a visually appealing site without knowing a single line of code.

But this convenience comes at a cost—the cost of control. These platforms are ‘walled gardens’, the digital equivalent of the command economy I described earlier. While you can easily arrange the pre-approved furniture, you can never change the layout of the house. The platform’s creators—a modern Politburo—decide which features are available, how much they cost, and what you can ultimately do with your own digital property. At any point, they can make a decision that doesn’t align with your needs, and you have no recourse.

What’s more crucial is the question of ownership. On these platforms, you are fundamentally a renter. Migrating your website away from their service is often difficult, if not impossible. With WordPress, you are the owner. You own your data, your design, and your content. You can pick up your entire digital presence and move it to a new host at any time, for any reason.

The difference is stark when you compare the ‘marketplaces.’ Look at the number of apps available in the Tilda or Wix directories. Now, compare that to the WordPress ecosystem, which boasts over 60,000 free plugins alone. This is the market economy in action: thousands of independent developers competing and collaborating to create the best possible solutions for every conceivable need.

The Human Element: Open-Source Community vs. The Algorithm

The conversation now extends beyond closed-source platforms to an even newer trend: AI website builders. Major providers promise a complete website in minutes, generated from a simple text prompt. The appeal is undeniable. If AI can eliminate the need for even LEGO-like block building, have we reached the end of the line for web developers?

Not so fast. While the speed of AI is impressive, we must look beyond the initial creation. For a simple online brochure, an AI builder might suffice. But for any entity that needs to grow, adapt, and stand out, the AI’s limitations quickly become critical obstacles.

The first issue is conformity. AI builders often produce generic sites from predictable templates. The second is rigidity; these platforms are typically even more of a ‘closed box’ than Wix or Squarespace. If you need a custom feature or a specialized software integration, you will almost certainly hit a wall.

This leads to a more profound problem, best captured by Lewis Carroll’s wisdom: in a living enterprise, “to be finished is to be dead”. A website is not a static product; it is a dynamic business asset. It requires ongoing maintenance, security updates, performance optimization, and strategic adjustments. AI cannot be your partner in this long-term journey. It cannot provide strategic advice on user experience, SEO, or how to adapt to emerging web technologies. An AI builder doesn’t understand your business goals, your target audience, or your vision. It executes a command; it doesn’t form a partnership.

This failing points to a fundamental limitation of artificial intelligence: a lack of semantics. Semantics is about meaning. While an AI is brilliant at syntactic tasks—arranging code correctly to execute a function—it has no true understanding of why it’s doing so. It can build a functional component, but it has no philosophical vision.

This is where the open-source community stands in stark contrast. The thousands of developers contributing to WordPress are not just executing tasks. They are driven by a shared vision and a deep, semantic understanding of the project’s principles. They debate, collaborate, and innovate because they believe in what they are building. AI is a powerful tool, but it is not a community. It cannot replace the collective human intent that drives a great project forward.

An Anecdote: Choosing My Plot of Land on the Web

The takeaway from this exploration is not to distrust convenience, but to understand its price. Proprietary platforms offer simplicity by limiting your choices. Open-source, on the other hand, hands you freedom—and the responsibility that comes with it.

This freedom brings us to a critical component: the toolkit. When you use a closed system like Wix, they provide the land (hosting) and the house (the software). With WordPress, you bring your own house and must choose not only the land but also the tools to build and maintain it. My own recent journey into this world was a series of lessons in making those choices.

As a newcomer at the start of this year, I learned by doing—and by making several ‘wrong steps.’ My first attempt was with Local WP, a fantastic tool that creates a complete web server on your personal computer. The catch? It runs on Windows, macOS, or a full Linux environment. My ChromeOS laptop, which lacks the necessary hardware support for a Linux container, couldn’t run it.

- “Lesson one: your freedom to choose is sometimes constrained by your own hardware.”

Next, I tried a cloud-based sandbox, InstaWP, which lets you spin up a temporary WordPress site online. It was web-based and promised to be fast. However, within hours of working with graphics, the environment became sluggish and unresponsive.

- “Lesson two: a temporary sandbox is not a substitute for a robust development environment or proper hosting.”

The most critical choices came with the editor itself. I was tempted by Elementor, a popular page builder known for its granular design control. However, a bit of research revealed it can create a ‘lock-in’ effect, where moving away from it in the future becomes incredibly difficult. This was exactly the kind of walled garden I was trying to avoid.

- “Lesson Three: Avoid the “Lock-In” Effect.”

Instead, I committed to the native WordPress Block Editor (Gutenberg). This led to the final, most important lesson: the tools you use should align with the core philosophy of the platform. The Block Editor is the future of WordPress. While it can theoretically work with any theme, the experience is dramatically better with a modern theme built specifically for it.

After some searching, I settled on the Kadence theme for its flexibility and lightweight performance. The key is to find a theme whose design philosophy clicks with you. If it feels like a struggle after a few hours, move on.

These weren’t mistakes; they were tuition payments for my education in digital freedom. The entire experience wasn’t a failure of WordPress—it was a masterclass in the responsibilities that come with its power. You have the power to build the perfect setup, but you must also accept the freedom to get it wrong and learn from the process. That is a privilege a closed system can never offer.

Final Thoughts: The Philosophy of Building on an Open Web

Choosing a foundation for a website, as we’ve seen, is far more than a technical decision. It is a choice that sits at the intersection of economics, philosophy, and personal autonomy. It’s the choice between renting a space in a centrally planned digital state or owning a plot of land in a chaotic, vibrant, and free market.

This single decision mirrors a larger question we all face in the digital age. We are constantly presented with a trade-off: the frictionless convenience of a closed ecosystem versus the demanding responsibilities of an open one. From the social media platforms we use to the smart devices in our homes, the ‘walled garden’ is becoming the default model for our online existence. Are we content to be passive consumers of digital experiences curated for us, or do we feel a desire—perhaps even a responsibility—to be active participants in building the web?

This question of human participation becomes even more critical as artificial intelligence offers to automate creation itself. What becomes of human intent? What is the value of a community’s shared vision when an algorithm can deliver a functional replica without a soul? The challenge lies in the very nature of creativity.

As Paul Melcher observes in his article The Last Creative Spark, ‘creativity is notoriously difficult to define…’, much like ‘beauty’ or ‘intelligence’. This is the semantic barrier for AI in its purest form:

Because we cannot formally define the concept, we cannot program a machine to truly understand its meaning.

This reveals a double-edged sword. On one hand, we can rest assured that a machine cannot replicate the nuanced, process-driven nature of true human creativity. On the other hand, many risk being mesmerized by its increasingly sophisticated facsimiles, convinced that a tool can substitute for a vision.

I don’t have the universal answers, but I have found my own. My choice to build with an open-source tool like WordPress is a vote for ownership, a commitment to the messy process of learning, and a belief in the power of a human community. It is more difficult, but it is unequivocally mine. And in the end, that is the only thing worth building.

Leave a Reply